by Carl Nellis, Associate Editor

‘It was impossible to establish the lay people in any truth, except the Scripture were laid before their eyes in their mother tongue.’

—William Tyndale [1]

The story of printing from the invention of Gutenberg’s press in 1450 to the work of the Reformers has been told and retold in every subsequent generation. This year, celebrations commemorating Luther’s bold act in Wittenberg in 1517 lead us to consider the whole period of the Reformation and the long legacy of that work we inherit today.

The story of printing from the invention of Gutenberg’s press in 1450 to the work of the Reformers has been told and retold in every subsequent generation. This year, celebrations commemorating Luther’s bold act in Wittenberg in 1517 lead us to consider the whole period of the Reformation and the long legacy of that work we inherit today.

In particular, we at Hendrickson Publishers look back to the Reformation as the early period where our own trade began to take shape, as publishers of thoughtful Christian books and, especially, as Bible publishers.

Sixteenth-century printers and publishers played a key role in the cultural shifts that made Luther’s choices possible and powerful. As Patricia Anders, Hendrickson’s editorial director, noted in her recent post on the continuing significance of the Reformation, “thanks to the invention of the printing press,” one of the forces that drove the Reformers’ work was the circulation of ideas through publishing. On the printed page, new ideas and new doctrines traveled from town to town in the native language of readers. As printing became more widespread, books could be produced at lower cost, at greater speed, and in higher volume. This large-scale production of knowledge created a new way of seeing and understanding the world, sparking an international movement, with provocative writers like Martin Luther lighting the way.

It wasn’t just Luther’s theological tracts and pamphlets, however, which set the German reading world ablaze. The Reformers’ embrace of the doctrine of sola scriptura, the belief that Scripture alone should guide Christians in their faith, put a new importance on believers reading the Bible in their own tongue without a human intermediary. The Reformers wanted truth established not in a magisterium, but in the heart and mind of every Christian. This desire found its full expression in the printing of German, Swiss, and English Bibles.

As these vernacular Bibles spread, the authority of church in Rome was undermined. New leaders such as John Wycliffe, Martin Luther, Jan Hus, and Huldrych Zwingli began to teach that no earthly arbiter need come between the believer and the sacred text. That made Bible publishing a dangerous business.

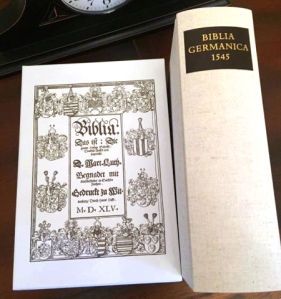

Martin Luther’s Biblia Germanica, 1545

In the years after nailing his Ninety-Five Theses to the doors in Wittenberg, while in hiding following the backlash against his work, Luther translated the New Testament into German. Published in 1522, Luther’s New Testament was not the first Bible to appear in German, as previous Bibles had been translated from the Latin Vulgate into High German. But it was Luther who dedicated himself to translate the Hebrew and Greek text “into the idiom of sixteenth century Saxony,”[2] thereby being the first to translate Scripture into the common language of his particular readers.

In the years after nailing his Ninety-Five Theses to the doors in Wittenberg, while in hiding following the backlash against his work, Luther translated the New Testament into German. Published in 1522, Luther’s New Testament was not the first Bible to appear in German, as previous Bibles had been translated from the Latin Vulgate into High German. But it was Luther who dedicated himself to translate the Hebrew and Greek text “into the idiom of sixteenth century Saxony,”[2] thereby being the first to translate Scripture into the common language of his particular readers.

In 1534, Luther’s whole Bible was printed in German for the first time by Hans Lufft, the “rising star in the Wittenberg printing scene” who  between “1534 and 1574 . . . produced thousands of Luther Bibles,” by some counts printing over one hundred thousand during that period.[3] Luther continued to revise his translation and correct errors, publishing various editions until the final, one-volume edition was published in 1545, one year before his death.

between “1534 and 1574 . . . produced thousands of Luther Bibles,” by some counts printing over one hundred thousand during that period.[3] Luther continued to revise his translation and correct errors, publishing various editions until the final, one-volume edition was published in 1545, one year before his death.

Working together with the German Bible Society in commemoration of Luther’s work, Hendrickson is now carrying a complete facsimile of this final, one-volume Bible. A recent episode of the Mortification of Spin podcast detailed the history of the Biblia Germanica. You can listen to the hosts “gawk over its beautiful calligraphy and . . . discuss God’s providential work through Martin Luther” at the Mortification of Spin website.

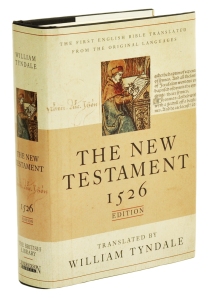

William Tyndale’s New Testament, 1526

In The Reformation: What You Need to Know and Why (forthcoming from Hendrickson in May 2017), Michael Reeves writes that before William Tyndale’s 1526 New Testament, “the followers of John Wycliffe had produced and read translations of the New Testament in English, but they were only handwritten,” and “impossible to mass-produce.” Like the German predecessors of Luther’s translation, they were “rather wooden renditions of the Latin Vulgate . . . and still contained all the theological problems of the Latin (‘do penance’ instead of ‘repent,’ for example).” Rather than copying his work by hand, Tyndale sent his work to Germany where it was

In The Reformation: What You Need to Know and Why (forthcoming from Hendrickson in May 2017), Michael Reeves writes that before William Tyndale’s 1526 New Testament, “the followers of John Wycliffe had produced and read translations of the New Testament in English, but they were only handwritten,” and “impossible to mass-produce.” Like the German predecessors of Luther’s translation, they were “rather wooden renditions of the Latin Vulgate . . . and still contained all the theological problems of the Latin (‘do penance’ instead of ‘repent,’ for example).” Rather than copying his work by hand, Tyndale sent his work to Germany where it was

printed off by the thousands, then smuggled into England in bales of cloth, and soon accompanied by his Parable of the Wicked Mammon, an argument for justification through faith alone. Even more importantly, Tyndale’s New Testament was a gem of a translation. Accurate and beautifully written, it was a page-turner. (16–17)

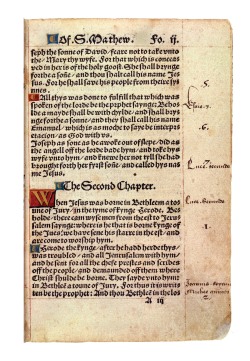

Hendrickson’s facsimile edition of Tyndale’s New Testament, produced in cooperation with the British Library, demonstrates the compact size and the beautifully decorated type of the original that delivered this translation to its first readers. At only six and a half inches high and four and a half wide, it was the perfect Bible for smuggling in a bale of cloth, and the brilliant color of its pages was well-suited to impressing the dissident clergy on the other side as they made the case for teaching the congregation in their mother tongue.

Hendrickson’s facsimile edition of Tyndale’s New Testament, produced in cooperation with the British Library, demonstrates the compact size and the beautifully decorated type of the original that delivered this translation to its first readers. At only six and a half inches high and four and a half wide, it was the perfect Bible for smuggling in a bale of cloth, and the brilliant color of its pages was well-suited to impressing the dissident clergy on the other side as they made the case for teaching the congregation in their mother tongue.

In 1535, Tyndale was caught by church authorities in Brussels and burned at the stake for his work on this “page-turner.” He was one of many who would die a martyr’s death during the Reformation, caught between the heat of his convictions and the flames of the so-called heretic’s pyre.

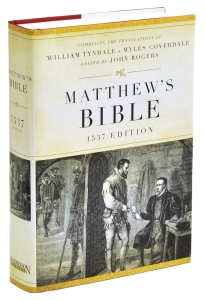

Matthew’s Bible, 1537

Tyndale’s death, however, did not suppress demand for the Bible in English, nor did it slow the advance of Reformation thought. In fact, in 1534, the same year that Luther first published his complete Bible, King Henry VIII made his separation from the church in Rome and claimed a new church for England with himself at the head. In 1537, as a part of this new day for English religion, King Henry ordered that an English Bible be placed in every church in England.

Tyndale’s death, however, did not suppress demand for the Bible in English, nor did it slow the advance of Reformation thought. In fact, in 1534, the same year that Luther first published his complete Bible, King Henry VIII made his separation from the church in Rome and claimed a new church for England with himself at the head. In 1537, as a part of this new day for English religion, King Henry ordered that an English Bible be placed in every church in England.

The Bible first used to fulfill that decree was the 1537 Matthew’s Bible, published by John Rogers under the pseudonym “Thomas Matthew.” Based on William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament and his partial  translation of the Old Testament, Matthew’s Bible filled in the gaps with the work of Miles Coverdale, who had completed an English Bible in 1535, translated from several sources including a Swiss-German Bible of 1529, the Vulgate, and Luther’s Biblia Germanica.

translation of the Old Testament, Matthew’s Bible filled in the gaps with the work of Miles Coverdale, who had completed an English Bible in 1535, translated from several sources including a Swiss-German Bible of 1529, the Vulgate, and Luther’s Biblia Germanica.

Basing his translation on Tyndale’s work, John Rogers suffered Tyndale’s fate. Like his predecessor, Rogers burned at the stake, becoming the first Protestant martyr under Catholic Queen Mary I when she ascended the throne of Britain in 1553.

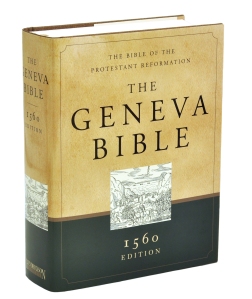

The Geneva Bible, 1560

The story of the Geneva Bible bears witness to the ongoing revolutionary potential of the English Bible as the first wave of Reformers passed the torch to the next generation. Translated and compiled by English Puritans who had fled England to shelter in John Calvin’s Geneva, the Bible was continuously printed from 1560 to 1640—eighty years of continued social upheaval and disruption that sowed the seeds of the English Civil War.

The story of the Geneva Bible bears witness to the ongoing revolutionary potential of the English Bible as the first wave of Reformers passed the torch to the next generation. Translated and compiled by English Puritans who had fled England to shelter in John Calvin’s Geneva, the Bible was continuously printed from 1560 to 1640—eighty years of continued social upheaval and disruption that sowed the seeds of the English Civil War.

It was in Geneva that Calvin continued Luther’s practice of developing strong relationships with skilled printers, who worked together with the Bible’s compilers to make significant advances in Bible publishing. Unlike its many predecessors, the Geneva Bible divided the scriptural text into numbered verses, used italic text to mark  English phrases not included in the original languages, placed marks over biblical names to aid in pronunciation, and included extensive textual and explanatory commentary in the margins.

English phrases not included in the original languages, placed marks over biblical names to aid in pronunciation, and included extensive textual and explanatory commentary in the margins.

The choices made in the layout and formatting of the Geneva Bible were the next steps of a dance between the need for believers to encounter the Bible on their own, and the need for scholars and church leaders to assist Bible readers in understanding the significance of the book for their own lives.

So familiar today, these choices in how a Bible could be presented to a reader reintroduced human interpreters into Protestant Bible reading, and raised significant questions about the role of the Bible in the life of a Christian. Readers who were puzzled about how to understand a passage could look to the commentary in the margin for help, but who wrote these notes, and could they be believed? They were printed next to the text of Scripture, but did they carry the same authority as the words of a priest, or even the head of the church? King James I, himself the head of the Church of England during his reign, loathed the assumed authority of the Geneva Bible’s marginal commentary so much that he “ordered his 1611 translators to confine themselves to cross-references and alternative renderings” when they used the Geneva Bible as a source text to create his “Authorized Version.”[4]

~ ~ ~

Wycliffe, Luther, Lufft, Tyndale, Coverdale, Rogers, Calvin, and King James I—from throne, pulpit, and printing press, these leaders of the Protestant Reformation all made their contributions to the ongoing discussion about where authority to interpret Scripture resides: in the text, the tradition, or the believer.

As spiritually, culturally, and economically significant today as it was during the Reformation, the printed Bible continues to be the most widely sold and widely read book. For that we have the courage of the Reformers, and their publishers, to thank.

[1] Quoted by Michael Reeves in “The Story and Significance of the Reformation,” The Reformation: What You Need to Know and Why (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, May 2017), 16.

[2] Introduction to “Martin Luther: Preface to the German translation of the New Testament (1522),” The Protestant Reformation, ed. Hans J. Hillenbrand (New York: Harper, 1968), 38. [3] Richard G. Cole, “Reformation Printers: Unsung Heroes,” The Sixteenth Century Journal (1984): 15:3, 334.

[4] Gerald Hammond, review of “The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution” by Christopher Hill, Translation and Literature (1994), 3, 155.

Carl Nellis is Associate Editor with Hendrickson Publishers. He lives in historic Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he reviews new books in critical cultural studies and researches contemporary American community formation around appropriations of medieval European culture. You can learn more about Carl’s work at carlnellis.wordpress.com.

Reblogged this on Zwinglius Redivivus and commented:

Neat stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jim!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Ayuda Ministerial/Resources for Ministry.

LikeLike